How to read a patent

Why would you want to read a patent anyway?

The system of patents was introduced in order to capture the vast mass of useful information that humans are producing on a daily basis. Thus, if you are a researcher or an aspiring entrepreneur, reading the patents of your predecessors and competitors can save you a lot of time.

Inventing something from ground up might cost you easily 2 full time employee years, while simply copying a existing solution could only take you a month. That’s a factor of 24 gained by simply reading and understanding patents from others.

Why do patents exist in the first place?

States have introduce the system of patents in order to capture trade secrets of their companies so that society can build upon that knowledge. In return for publishing these secrets, the companies enjoy a time-limited protection for using their invention. Only the holder of the patent has the exclusive right to use this invention. The company can either use it straight-away in a product it is selling, or simply block a certain field for competitors or it can license the patent out and earn money directly on the inventions.

But how would I then read and understand a patent?

Patents are often structured in the same way: they contain a title and a summary, some background, the description of the invention, possibly some citation of earlier works, often some drawing and in the end the actual claims the holder of the patent will have if the patent is granted.

The easiest to start with are the drawings and any descriptions that are related to them. For simply lay people (i.e. not patent attorneys), this information is the easiest to grasp and gives you often already a sufficient idea of whether the patent is interesting for you or not.

Claims

If you need to dig deeper, turn to the claims. The claims define which invention is actually protected by the patent. The claims itself are structured in independent and dependent claims.

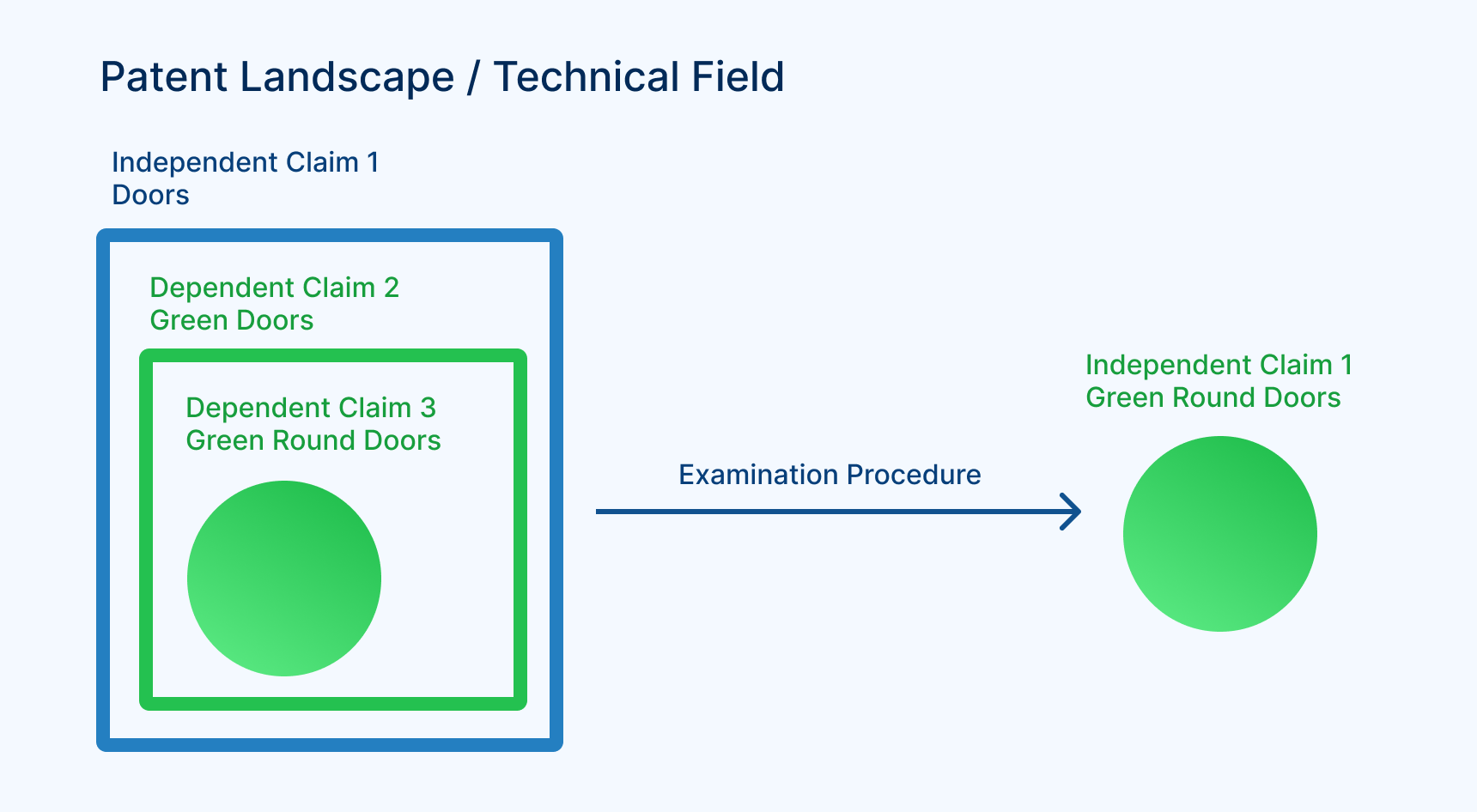

The independent claims (often just one or two) define the maximal protection scope of the patent. They are often the most useful to know that a patent is really about. The dependent claims which refer back to the previous (independent claims) further limit the protective scope of a patent. So, they are useful in edge cases to find out whether your invention or product is covered by a patent or not anymore. See below for an example on how a patent on doors in limited to first green doors and then green round doors.

Overlap or not?

So how can you then determine if an invention or a product of yours falls within the protection scope of a patent? If any of the described features in the claims is not present in your product, your product is not covered by the patent.

Claims during the examination period

If you want to go one level deeper, look how the claims evolved during the examination period. When a patent application is first handed in the claims often just contain independent claims. During the examination, the examiner will complain that the claim has been formulated too wide (since you want your patent to be as wide as possible) and the applicant will have to introduce dependent claims to limit the protective scope until the examiner is satisfied.

As a simple example: let’s assume you try to patent doors as “devices hinged on the wall of houses that can open and close an opening in said wall”. After handing in your application, the examiner complains that this is not original enough. So you limit the scope further to only “green doors”. The examiner is still not happy, so you limit the scope further to “green round doors”. Now the examiner is happy. Often, the claims are then rewritten one last time and the previous dependent claims (2 and 3 on our example) are incorporated into the independent claims (1 in our example).

You can see immediately, how this might lead to your product dropping out of the scope during the examination (your doors are green but not round; thus not complying with all features in the patent) or during further product development (you start selling red doors; thus again not complying with all the features in the patent).

Following the examination procedure has the added benefit that you can see where the patent might have weaknesses as the examiner with certain points. So this shows you immediately which features determine with a high likelihood whether your product falls under a protective scope or not.

Conclusion

So, there are three levels to read a patent.

- to understand a patent quickly, simply check the drawings and any description related to the drawings (there are often references).

- To deepen the knowledge, check out the independent claims or even the dependent claims.

- If you want to explore the deepest levels, check the other parts of the patents and even how the claims have changed during the examination procedure.

Read the patent on the level you need, depending on how much a patent is related to your interests.

< Zurück zu allen Blogposts